Tetris Clone

2020-05

I did this project one week when I neeeded a break from my bigger projects. I decided I wanted to get a visceral feel for how hard it is to finish a game; surely it’s pretty hard? But how hard? So I decided to clone Tetris (the gameboy version) down to a tiny level of detail to see how much work it would take.

Turns out, it takes a lot of work :) But I learned a lot! I haven’t published this project publically (for licensing reasons), but I’ll walk you through some of the highlights in this post.

prototype versus polish

To start this project, I used my custom C++ Windows engine and quickly built a basic Tetris prototype. I’ve built tetris plenty of times before (it’s often the first thing I make when I’m trying out a new engine) so it wasn’t hard to get the basics up and working:

(The tile sprites were recreated by cobbling together a bunch of screenshots, and the music/sfx are mp3 recordings, but everything else in this project was handmade on top of the Windows API.)

This is often the point where I lose interest and stop working on a project; I’ve sketched out the basic idea and I think it’s cool, but I don’t put in the time and effort to polish a prototype up and publish it for other people to play. However, I had already decided I was going to really polish this game, to learn for myself what sort of effort that actually takes.

I chose to exactly clone an existing game (gameboy tetris) so that I wouldn’t need to make any design decisions that might lead me into distracting rabbitholes – I would only need to exactly clone an existing game.

gosh this is hard

So, it turns out that finished games have, like, animation and stuff. And a menu, and a pause screen. And score. My prototype code really creaked and groaned as I tried to add these sorts of things. For instance, I had shortsightedly stored the game blocks only in the tilemap object, which was also used to display the screen. So when you paused the game, a pause screen was displayed, which overwrote the tilemap… so when you unpaused, all of the blocks were gone! Whoops.

Animation in particular was rough – I knew for a long time that I would need to recreate the little laser effect that happens when you clear a line, but I kinda of dreaded having to write code that worked across multiple frames like that. (I know now that what I really wanted here was coroutines, which is not easy to do by default in C++.)

many hours later

Check out this line clear animation! I’m happy I figured out a clean way to do the animation (see the upcoming “state machine” heading for a brief explanation), but also: check out the way that the blocks fall down after the laser animation ends! They don’t fall all at once; they’re staggered, two rows at a time. I played many hours of this version of Tetris as a kid, but had I never explicitly noticed this until working on this project.

the tetris font <3

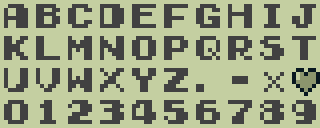

Let’s talk for a moment about the amazing, chunky font Tetris uses. Look at it!

It’s too good! I love it. Most letters have their weight emphasized on the right side, which seems backwards from what I would expect.

And look at the numbers!! Look at how CHUNKY the 9 is! It’s got a solid 3 by 4 section of pixels filled on the right, while the left side is a tiny unconnected 1 by 2! It’s too good! This font just has so much character and I love it.

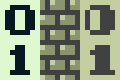

I have a slight correction from earlier – I said I was building a clone, and I wasn’t going to change anything. But… look how boring the 0 and 1 are in comparison to the rest of the font!

There, much better :)

state machines

A state machine is a mathematical model for representing something’s “state”, like whether a monster is currently wandering aimlessly or actively hunting down the player. If you really math it up, you’ll end up in some very cool places, but for most games, state machines don’t feel like math, they just feel like setting a variable to one of many values defined in an enum. So why am I talking about them here?

Well, adding a state machine to track the current “game mode” was a huge win for this project. Writing code to do any one thing is generally easy, but if you ask me to write understandable, maintainable code, I’ll need to set up some sort of organization and code architecture that makes me confident that the codebase isn’t eventually going to come crashing down under its own weight. If your code is all together in one jumbled mess, it becomes hard to edit any single part of it; you just know in the back of your mind that you’ve accidentally broken something far removed from what you’re currently changing.

In my final Tetris clone, the game can be in any of these different states (“modes”):

enum game_mode {

GM_NONE, // dummy state, used during game startup

GM_PLAY, // the player is playing the game

GM_LINE_CLEAR // a line clear animation is in progress

GM_PAUSE, // the game is paused

GM_LOSE, // the "you lose" animation is in progress

GM_HIGHSCORE, // the player is on the highscore screen

GM_COPYRIGHT, // the game is starting up and the

// copyright notice is onscreen

GM_TITLE, // the game is on the title screen

GM_REC_DEMO, // a dev mode, used to record the demo video

GM_DEMO, // the game is playing a demo game

// (triggered when the player idles for 40

// seconds on the title screen)

GM_TYPE_SELECT, // the player is chosing what type

// of game to play

}

Every frame, a different update function is called depending on the game’s current state:

void GameUpdate(game_state *State) {

switch (State->Mode) {

case GM_PLAY: return GameUpdate_ModePlay(State);

case GM_LINE_CLEAR: return GameUpdate_ModeLineClear(State);

case GM_PAUSE: return GameUpdate_ModePause(State);

case GM_LOSE: return GameUpdate_ModeLose(State);

case GM_HIGHSCORE: return GameUpdate_ModeHighScore(State);

case GM_COPYRIGHT: return GameUpdate_ModeCopyright(State);

case GM_TITLE: return GameUpdate_ModeTitle(State);

case GM_REC_DEMO: return GameUpdate_ModeRecDemo(State);

case GM_DEMO: return GameUpdate_ModeDemo(State);

case GM_TYPE_SELECT: return GameUpdate_ModeTypeSelect(State);

default: { assert(0); } break;

}

}

Now, this is all very standard, well-known game architecture, but I also added in one maybe less-known tip that I got from a mailing list post by John Carmack:

If a function is called from multiple places, see if it is possible to arrange for the work to be done in a single place, perhaps with flags, and inline that.

What does this advice look like in the context of state machines? Instead of calling a TransitionMode(GM_LINE_CLEAR) function that immediately changes the State->Mode to GM_LINE_CLEAR, I instead set a variable State->NextMode to GM_LINE_CLEAR. Only much later, after the frame has finished, does my engine finally update the game mode to the value of State->NextMode.

To sum up, State->Mode is only changed in between frames. This made the resulting code so so easy to reason about – I had the freedom of being able to add new states at will, but because I constrained myself to stay fixed in a single game mode for the duration of any given frame, this state system had very low mental overhead and made it easy to think through what my code was doing.

I’ve used this sort of single-transition-point state machine in basically all of my games since.

wrap-up

That’s it! This was a fun project, and it taught me the things I wanted it to teach me. I went into it thinking “okay I’ve already made a working Tetris clone here… how much more, exactly, is there to do?” and the answer was, of course: a lot!

There was a really fun period in the middle of development where I would occasionally be playing my clone, and I would be surprised when something wasn’t implemented exactly right, because I thought I had been playing the emulator instead!

I haven’t published this publically (for licensing reasons), but the video below should show off most of it. Here’s the list of known differences between my version and the original version:

- My version doesn’t have a “B-TYPE” mode implemented

- My version has some minor sound glitches/differences

- My version chooses which pieces are coming next in some arbitrary random way. Tetris RNG algorithms are varied, and have an important impact on strategy; I wish I’d taken the time to make the RNG for my version match the original version, but it slipped my mind.

- My version doesn’t have a “you win” animation that plays when you get over 100,000 score. (I had no idea this existed until doing this project! I stumbled across it while I was testing the score system / tetris multiplier.)

- My version has a slightly different 0 and 1 in the font :)